Brown Recluse Bites (Loxoscelism)

Ashley Zeoli and Matthew Kern

Background

- Only a handful of spiders are truly harmful to humans

- The brown recluse (a member of the Loxosceles genus) is widespread in the South, West, and Midwest US

- They are often found in homes (attics, basements, cupboards) and outdoors (rock piles and under tree bark)

- Their numbers increase in association with humans (i.e. synanthropic)

- Appearance/identification:

- Three pairs of eyes, a monochromatic abdomen and legs, very fine hairs on legs

- Using the “violin” pattern on its body is a poor way to identify this spider, as other harmless spiders can have similar markings

- Loxoscelism is the medical manifestation of the brown recluse spider bite

- Venom contains insecticidal toxins, metalloproteases, and phospholipases

Presentation

- Bites are most common on the upper arm, thorax, or inner thigh

- Local signs:

- Usually painless, but can cause burning sensation with two small cutaneous puncture marks with surrounding erythema o Usually appears as a red plaque or papule with central pallor, sometimes with vesiculation

- Usually self-resolves in 1 week

- Skin necrosis (10-20% of cases): o Lesion can progress to necrosis overall several days

- An eschar will form that eventually ulcerates o Usually will heal over several weeks to months

- Systemic signs (rare, but more common in children):

- The degree of systemic effects does not correlate with the appearance of the bite

- Symptoms develop over several days, and include nausea, vomiting, fever, rhabdomyolysis, malaise, acute hemolytic anemia, significant swelling from head/neck bites that can compromise the airway, DIC and renal failure. Myocarditis is a rare adverse effect that may occur.

Evaluation

- Presumptive diagnosis is based clinical presentation of the bite/wound

- DDx includes vasculitis, pyoderma gangrenosum, cellulitis, or other arthropod bites

- Definitive diagnosis is based upon observing a spider bite in combination identification by an entomologist

- Patients with local symptoms do not need any further workup

- Patient with any systemic symptoms require lab evaluation for more serious disease:

- CBC, UA to eval for “blood” without RBCs, CMP, CK

- If anemia: Type and Screen, peripheral smear, reticulocyte count, LDH, haptoglobin, coags to evaluate for hemolysis or DIC

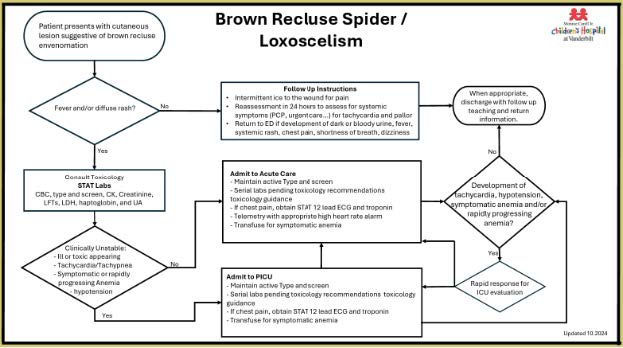

Flowchart of management protocol borrowed from VUMC Children’s Hospital.

Management

- Local signs:

- Wound care (soap/water, elevation)

- Pain management

- Tetanus vaccine/prophylaxis if indicated

- Antibiotics only if signs of concurrent cellulitis

- Skin necrosis:

- Symptomatic and supportive care

- Surgical intervention can worsen cosmetic outcomes and is rarely indicated in the acute care setting. Skin grafting is occasionally needed for a very large ulcerative wound that is not healing. Infection is rare, Furthermore, the ulcerative base of the wounds often have a yellow stringy material that is not pus or infection. Please call Toxicology with any questions regarding brown recluse bites

- Systemic signs: Targeted at treatment of symptoms that develop (Consult toxicology)

- Hemolytic anemia: generally, transfuse to keep hgb > 9-10. However, the rapidity of hemolysis is more important than the hgb for determining when to transfuse but almost always the threshold is higher than other forms of anemia.

- Rhabdomyolysis: LR for UOP >200-300cc/hr

- If patient develops chest pain: obtain EKG and check a troponin; if either is abnormal please obtain echo and call Toxicology as heart effects (i.e. myocarditis) is something we have been seeing at VUMC

- DIC: supportive care